This is the annual post where I basically go through all the notable and interesting games I played this year, wax poetic about them, and create new forms of hyperbole to describe my personal games of the year. Last year’s post can be found here, and previous year’s posts can be found on my high school blog, which I’m keeping hidden for all the reasons.

2013 will be remembered for two major movements within gaming: the rise of the American e-sports scene, and the proliferation of the queer games scene. I don’t belong to either of those scenes per se, but their growth is cause for celebration: the diversification of scenes to include people outside of that mainstream “gamer” community means that more and more people will become “gamers”, which is what I’ve always wanted. I hope to see soon a world where there will be a scene for every imaginable type of person, and I believe we’re making strides in that direction.

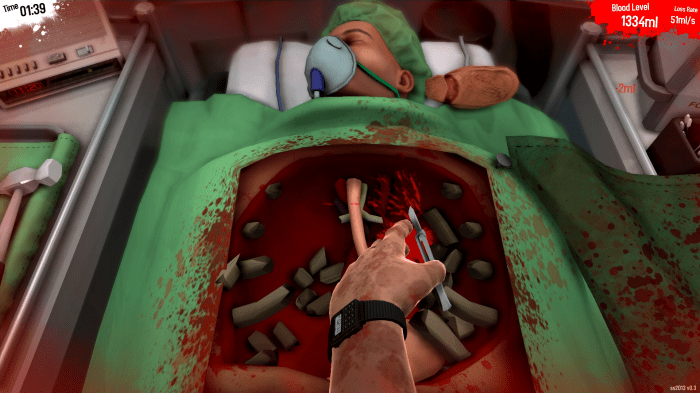

Just a year ago, we entered a period of unprecedented change to how games are made, processed, and understood, leading to the proliferation of newfound developers, genres, subject matters, and modes of play. Now, that trickle of change has grown into an avalanche, and the game industry that exists today welcomes with open arms games like Surgeon Simulator, Gone Home, and The Stanley Parable.

Five years ago, the thought of a world like this would have been unimaginable.

Meditating on change in the industry, the importance of our place in time, and the potential we now have to steer the course of gaming’s destiny is something that I’ve done in previous posts, and really, I’m just repeating myself here. But I can’t help but reiterate my enthusiasm: this is the gaming world that I’ve always wanted to live in. In 2010, I yearned for more daring games unafraid to try something different and interesting, and in 2013, those games exist everywhere I look.

DEAD GAMES WALKING

Telltale’s hit point-and-click adventure The Walking Dead was the first game that I played this year, and one of the most emotionally taxing games that I’ve ever played. Its a story-driven game about leadership, the core mechanic of navigating dialogue trees is contextualized in a way that every decision carries great ethical weight, asking players questions not like “what is right or wrong?” but rather “who do I want to hurt least?”. Telltale manages to maintain this sense of constant heft and weight throughout the game’s five episodes, concluding in a cathartic, heart-wrenching ending that left me drained, shaken, and worn.

Next was The Unfinished Swan, a game by USC IMD alums Giant Sparrow, a first-person puzzle game that iterates upon its core mechanic beautifully. The Unfinished Swan is videogame comfort food, it’s a heartwarming, homey tale that makes you feel all warm and fuzzy and loved inside. As I played this game with my friends, I couldn’t help but subconsciously maintain a splendid grin throughout the entire experience.

Shortly afterwards, we played through Shadow of the Colossus, a monumental achievement of the sixth console cycle, which holds up with remarkable grace. The vastness of the gameworld dwarfs the player’s tiny, insignificant avatar, imbuing exploration with a tangible sense of forlorn loneliness. The giants which walk the Forbidden Lands trot with a quiet, fearsome majesty. Each battle with a Colossus carries a hefty emotional arc, ranging from the apprehension of the approach, the confusion and panic of trying to discover the beast’s weakness, the empowering, triumphant thrill of learning that weakness, and the catharsis… then sadness, of victory. Incredible game, definitely an annual playthrough for me.

Surgeon Simulator 2013 is the game most indicative of where we stand in the history of this medium today. Here, we have a game developed in 48 hours at the 2013 Global Game Jam, a series of once-underground game-making competitions. It was not funded not by publisher, nor Kickstarter campaign, nor grant money. Surgeon Simulator wasn’t even a good game by traditional measures of design, featuring an intentionally unintuitive control scheme, the game is in essence an interactive joke. By all prior standards of game funding and publishing, Surgeon Simulator 2013 should have been quietly forgotten amongst the hundreds of games designed at these events. And yet, through an unforeseen wrinkle in how this world works, Surgeon Simulator was reviewed higher, and sold better, than AAA sequels like God of War: Ascension, Crysis 3, and Gears of War: Judgement. Consumers are changing, and are now welcoming new games willing to challenge long-encoded standards of design, making room for games about butterfingered surgeons. Its an underdog story so glorious that it could have only happened by accident.

“X IS A METACOMMENTARY ON Y”

In March, Bioshock Infinite, a game which I had eagerly anticipated for years, finally came out. It was the week of GDC, and all my game studies classes were cancelled, so I completed the game in a day. While upon reflection, the game is brimming with design and narrative flaws so basic that it’s a wonder how it passed playtesting, I found Bioshock Infinite to be an enjoyable, albeit overhyped and subsequently disappointing, shooter. My enjoyment of it came mostly out of its uniquely postmodern subtext, which challenges the notion of meaningful choice and autonomy in story-driven games. My analysis of it, which got featured on Gamasutra, has become basically my only claim to fame.

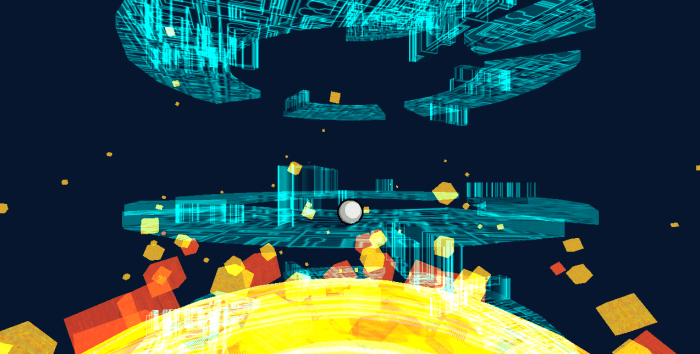

Next up was the delightful FEZ. Like many, I discovered FEZ through Indie Game: The Movie and was tightly invested in Phil Fish’s painful, triumphant, underdog story. FEZ was fantastic with its daring experimental structure and wondrous difficulty. FEZ’s obscure puzzle designs and interdimensional platforming harkens back to memories spent of school playgrounds, secrets and rumors of the Mew under the Viridan City truck and the Triforce chest in Forest Temple spread like gossip. FEZ is a game meant to be played in parallel with a good friend, sharing every delightful discovery along the way with childlike wonder.

I didn’t know what to think of The Last of Us when I first learned about it a year ago. A third-person action game set in the zombie apocalypse featuring an old guy and a girl seemed pretty unoriginal given Naughty Dog’s fantastic pedigree, and thus, I went into it with doubts. When I finally played it, I found it unique and incredible in a multitude of ways. Combat is disempowering, limited resources and a relatively underpowered protagonist lends the game a sense of dread and despair that gives way into a panicked chaos of gunfire, culminating in the cathartic release of survival. The game’s story, one of the strongest told this year, calls into question the social demarcations separation “us” and “them” and meditates on themes of love and sacrifice.

Thomas Was Alone was one of the cutest games I’ve ever played. It is both one of the best puzzle-platformers to come out of a scene rife with them and perhaps the best demonstration of gameplay-as-metaphor and the proceduralist aesthetic to have come out this year. The way it characterizes its quadrilaterals and lends them personality through kinaesthetics and functionality elevates this puzzle-platformer into a delightful story about friendship, jealously, need, and identity. Thomas Was Alone’s rectangles undergo entire character arcs with meaningful conflicts and conclusions, and the game communicates those arcs through simple game feel, lending its characters a humanity not seen in all the dialogue trees and facial animation systems developers have produced thus far.

GO HOME

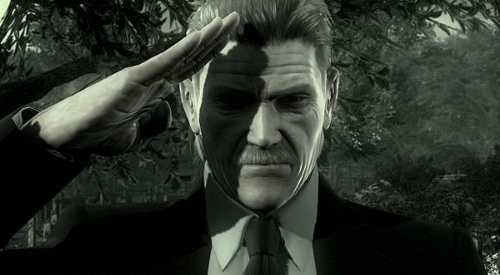

I disliked Metal Gear Solid when I first played it, but decided to give the series a second go after studying writing about postmodernism, a cultural aesthetic that the series adheres to very much. Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater, which sheds the series’ cyberpunk postmodernism to focus on a Cold War-era spy fantasy, changed my perspective on the series substantially. A delightfully Japanese pastiche of 20th century spy fiction, Metal Gear Solid 3 is perhaps the most restrained and grounded game in the series (which is not saying much given Kojima’s predilection for vampires, cyborg-ninjas, and the Illuminati). Every room in Snake Eater‘s vast world is a playground for emergent strategies for traversal, coupled with a variety of tools from guns, to chloroform rags, and alligator hats, Metal Gear Solid 3’s sneaking system is an incredible sandbox for self-expressive play.

Standards for environmental storytelling have shot up over the course of the generation. Flavor text that was communicated by pressing the “interact” button next to an object is now communicated visually, through intricately detailed 3D models in a gameworld. The juxtaposition of objects creates place and story, and narrative discovered rather than delivered. This made traversal through the beautiful environments of The Last of Us, Bioshock Infinite, and Metroid Prime a delight, and it is wonderful to see a game like Gone Home emerge from this burgeoning tradition. Evoking nostalgia for the nineties, Gone Home communicates a tale about a family that underwent a great change while its older daughter was off at college. The means of progressing through the story is snooping through the spaces each family member inhabited. Characters go through entire character arcs as the player creeps down a hallway, the catalysts for their change evident in the things they carried. Its a tough game that dances in and out of some uncomfortable themes, many of which strike close to home, and one of the most structurally interesting games of the year.

On the complete opposite side of the gaming spectrum, XCOM: Enemy Unknown consumed a substantial amount of my time early in the semester. Its an incredibly difficult, incredibly addictive turn-based strategy game that maintains a constant sense of desperation in every aspect of its design. The dread can become overwhelming as players become strapped for time, resources, and personnel, lending dramatic weight to every single decision. The death of a single high-ranking soldier from a stray bullet can cause entire plans to crumble in an instant. But when the dice land in one’s favor and a plan goes perfectly as intended, the triumphant rush of victory is unparalleled.

Kentucky Route Zero is surreally magnificent, and maintains a consistency of vision that bleeds into every single corner of its dreamy aesthetic. It is a magical-realist point-and-click adventure game with art inspired by late 20th-century theatrical set design and poetic writing imbued with a nostalgic sense of Americana. It’s as if Steinbeck’s sentimental prose met the magical wonder of Rudolfo Anaya’s, creating a spiritually evocative tale of Conway’s journey down the Zero’s rabbit hole. For anyone even mildly interested in the unusual, Kentucky Route Zero‘s whimsical and forlorn world is one worth exploring.

Personal Game of the Year

Naming a personal game of the year is a substantial ordeal for me, simply because I feel a sense of guilt for overlooking all the great games that I considered for it, especially in 2013, a banner year for unusual and interesting games: digital, physical, analogue, and installation. And in the shadow of that regret, I must name The Stanley Parable as my personal game of the year.

Yes, systemically speaking, The Stanley Parable might not even be a game, academic standards of language and game studies considered, it fits more under the umbrella of interactive fiction than videogames, but that’s beyond the point. The point is that The Stanley Parable is interesting.

If Bioshock Infinite called into question ideas of the existence of autonomy in an authored piece of fiction, then The Stanley Parable takes that metacommentary to its intellectual extreme, calling into question ideas of player motivation, narrative structure, meaningful choice, the lusory attitude, the player-avatar relationship, freedom in authored fiction, and the conflict between player and designer. The game posits those questions in short, fifteen minute bursts that demand reflection and study, performing its commentary more elegantly than Ken Levine’s bloated, frustrating shooter ever could.

Look, the core mechanic of the Stanley Parable is making binary choices to influence the outcome of a story, which in itself isn’t very interesting, essentially being tantamount to any number of terrible dating-sims. But when contextualized with questions about narrative structure and game design, The Stanley Parable‘s mechanics become ironically rife with meaning, evolving into the catalyst for engaging conversation. While many may rightfully criticize The Stanley Parable for not being a game per se, that does not make it any less interesting as a piece of interactive media, and in a period where all we’re asking for are games that take daring risks, engage with challenging themes, and are in essence unique and interesting, isn’t The Stanley Parable exactly what we wanted?

Thank you and Merry Christmas!